A Brief History of Sustainable Investing

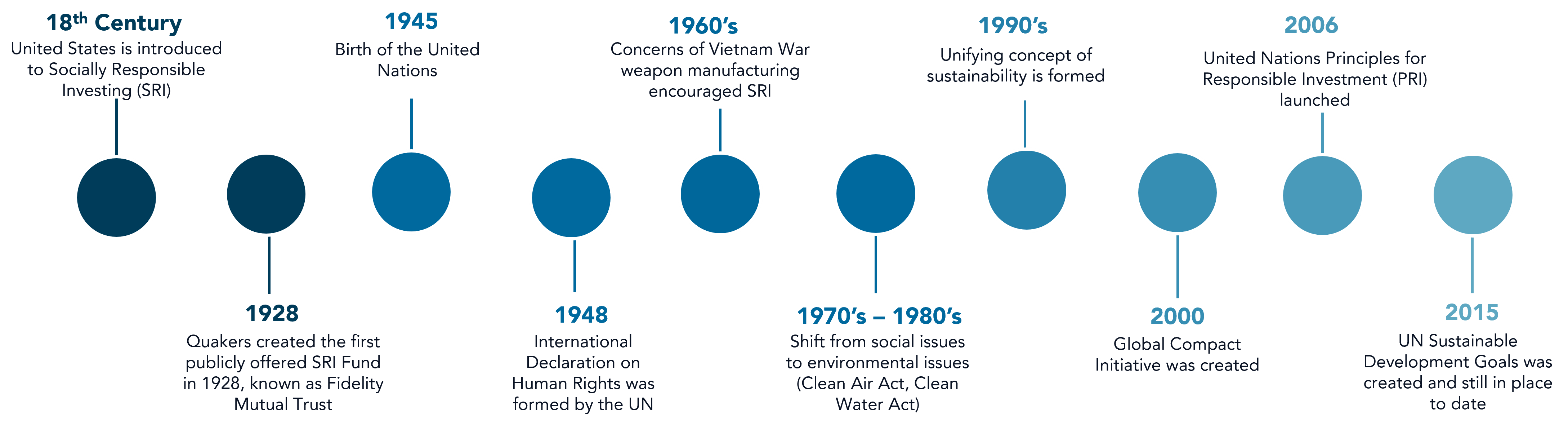

Sustainable investing as a practice has experienced rapid growth over the past decade as many investors have realized the significant impact companies have on our environment, society, and governance. Many people think of sustainable investing, often interchangeable with Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) investing, as a new method of investing, however the ideology in the United States is as old as the nation itself and the philosophical ideology has long been established across continents and religions for thousands of years. In the United States, socially responsible investing (SRI) first took form during the 18th century when the Methodist Church urged its members to refrain from investments in controversial companies including those in the alcohol, tobacco, weapons, and gambling industries .[1] The Quakers were also pioneers of SRI. The Quakers were known to be vehemently against slavery and war, and with these principles they created they created the first publicly offered SRI Fund in 1928, known as Fidelity Mutual Trust.[2]. This later became the Pioneer Fund and in 1950 began applying additional SRI screens to avoid tobacco, alcohol and gambling stocks. The avoidance of “sin” stocks in the 1950’s marked the beginning of the rise of modern socially responsible investing, with each decade sparking a new group of socially concerned investors.

Shifting the Investment Focus

While morally oriented investment practices dominated the early iterations of responsible investment through disinvestment as a primary methodology, the concept of human rights began to take a more secular form in a non-religious geopolitical context through the birth of the United Nations in 1945. The United Nations would effectively chart the future path with the International Declaration on Human Rights in 1948, establishing a common standard of human rights that should be protected across all nations. While not directly created for the purpose of investment standards, the United Nations approach to sustainable development through the lens of human rights established an important milestone in the historical development of the investment approach.

The geopolitical forces of the 1960’s continued to encourage SRI, largely driven by concerns about the Vietnam War. The level of dissent was increasing throughout the country, prompting many to realize that companies were profiting from this controversial war effort. Those who protested against the Vietnam War began to boycott companies that manufactured weapons for the war. Along with this, several groups of students demanded that university endowment funds cease investing in defense contractors. The civil rights movement resulted in increased attention around social, environmental, and economic issues that previously had only been discussed in certain activist groups.

In the 1970’s, however, the investment focus began to move away from social issues toward environmental issues when in April of 1970, the first Earth Day Celebration was held, forcing the government to acknowledge certain environmental problems that needed to be addressed through legislation. Several landmark environmental legislations took effect during the 1970’s, including the creation of the EPA, the Clean Air Act of 1970, the Clean Water Act of 1972, and the Ocean Dumping Act in 1972.[3] Originally enacted in 1963, the Clean Air Act of 1970 was a major milestone as it gave the EPA the authority to set and enforce national air quality, auto emission, and anti-pollution standards. Prior to the Clean Air Act, there was no legislation that gave the government direct authority to regulate air pollution. Additional SRI mutual funds also were created during this time, with the Pax World Fund, the First Spectrum Fund, and the Dreyfus Third Century Fund all being founded in the early 1970’s.[4]

However, in the 1980’s geopolitical human rights atrocities and global poverty continued to boil in the background. Apartheid started to become a worldwide issue that couldn’t be ignored, prompting activists and major institutions to take action to make their anti-Apartheid positions clear. Many decided to take proactive measures to divest themselves from South African investments. In 1985, students at Columbia University formed a sit-in, ordering that the University stop investing in companies that have operations in South Africa. All these actions paid off when in 1986, Congress passed the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act which banned new investment in South Africa. Because of this, more than $625 billion was screened and redirected from South Africa by 1993.[5]

In addition, the 1980’s featured several major environmental disasters such as Chernobyl and the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill. While extremely unfortunate, these events helped spur the creation of two noteworthy organizations, the United States Sustainable Investment Forum (US SIF) and the Coalition for Environmentally Responsible Economies (CERES).The Valdez Oil Spill in particular united the environmental and social investing community to create the Valdez Principles – a voluntary list of 10 guidelines for large companies to sign.[6] In addition to these organizations, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change was created in 1988. By this point, social responsibility issues had become an increasingly popular subject among activists, investors, and political institutions.

The Unifying Concept of Sustainability

During the 90’s, the disparate concerns around poverty, inequality, human rights, corporate responsibility and environmental degradation finally culminated into a broad doctrine of “sustainable development.” Many global organizations acted as SRI became more prevalent. In 1990, the Domini Social Index was created, which is now known as the MSCI KLD 400 Social Index.[7] The index consists of 400 companies that meet certain social and environmental standards, making it the first capitalization-weighted index that tracks sustainable investments. Shortly after this, in 1992 the UN held the Conference on Environment and Development, bringing environmental issues to the forefront when previously they were considered less pressing issues among the UN community through the declaration of the Agenda 21, an action plan created to achieve sustainable development. By 1994, there were 26 funds with a sustainable element to them totaling $1.9 billion in assets.[8] In 1997, The Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was held in Kyoto, Japan. From this conference, the Kyoto Protocol was crafted. The Kyoto Protocol addressed global warming by setting greenhouse gas emissions targets for each signing country.[9] This was the first real push for international cooperation on global warming. In the first signing period, 84 countries signed commitments to reduce emissions. In 2000, the Global Compact Initiative was created for investors to focus on human rights, environmental, labor, and anti-corruption principles. Within the same year, the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) was launched which sets reporting standards using ESG metrics. The GRI’s reporting framework is widely used among the largest global companies, with roughly 40% of US companies and 60% of European companies utilizing their standards.[10]

The Road to Accountability Through Metrics and the Birth of ESG

By the early 2000’s, sustainability had amassed a large group of proponents that led to the introduction of several major initiatives and organizations. In 2006, the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) launched, further developing the sustainable investing landscape. Currently the PRI has over 4,000 signatories made up of asset managers and institutional investors representing over $120 trillion of assets.[11] However, PRI signatories were faced with the challenge of proving their commitment through metrics. So, as metrics evolved, they were grouped into the environment, social and governance buckets for ease of categorization, giving rise to the more common acronym, ESG.

In the push to create metrics, regulators in California, New York, and Washington began to require climate risk disclosures by insurers operating in their states. With this influx of environmental initiatives came some social and governance initiatives as well. The Workforce Disclosure Initiative (WDI), aiming to provide greater disclosure and accountability surrounding workforce issues, was created in 2008. Today the WDI has 141 companies participating with over $7.5 trillion in AUM.[12] With regard to governance, the 30% Club was established in 2010 which is led by female executives and strives to achieve gender diversity by aiming for at least 30% representation of women on all boards and C-suite executives globally.[13] As more organizations continued to bring ESG issues to the forefront, more investors recognized that their fiduciary duty not included ESG considerations, but more importantly, failing to integrate these long-term risks into their investment decisions could constitute a potentially material breach of fiduciary duty.

By this point, corporate America began to incorporate ESG into their operational practices as well as into their governance. However, there continued to be a lack of uniform metrics and standards, making it very difficult for ESG investors to compare companies. The Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) attempted to solve this issue. SASB created industry metrics that track the impact of environmental issues among companies by industry. SASB created these industry-specific metrics to help achieve standardized reporting of ESG data. While SASB is a step in the right direction, the lack of standardization among companies continues to be a major talking point among the ESG investing community.

Standardizing the Goals

Perhaps one of the most influential components to ESG investing today is the creation of the UN Sustainable Development Goals in 2015. The SDGs are constantly cited by companies, institutions, organizations, and countries as they are the most widely accepted goals to date. The SDGs consist of 17 goals and 169 targets to be met by 2030. Many of these goals are very ambitious and will likely not be met by 2030. However, governments, companies, and countries will likely continue to use them as progress indicators in their sustainability endeavors even after 2030. In the same year that the SDGs were created, the Paris Agreement was drafted. Today, the Agreement has been adopted by almost all countries, with Turkey, Iran, Iraq, Libya, Eritrea, and Yemen as notable exceptions.[14] The Paris Agreement was specifically created to combat climate change, with the central goal being the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions to keep global temperatures from rising above 2 °C. Each country is responsible for setting its own emission-reduction targets which are reviewed every 5 years. While previously climate change had been a topic frequently discussed within the international community, this was the first legally binding treaty on climate change where all countries agreed to take concrete action to reduce their emissions.

Around this time, action was being taken within the investment community to reduce emissions as well. In 2017, the Climate Action 100+ was established. The Climate Action 100+ is an investor initiative made up 617 global investors who engage with and assess the world’s largest companies’ progress towards tackling climate change. 167 companies making up $10.3 trillion in market cap are part of the initiative. Approximately 80% of global industrial emissions are estimated to come from the 167 participating companies.[15] The Climate Action 10+ likely served as a catalyst in the growth of ESG investing as investors started to hold companies accountable for their environmental practices. By this time, ESG had become a fundamental part of investing for many asset owners and managers.

Standardizing the Disclosures

If standardizing the goals is the first step, the next step must be to standardize how to monitor and measure progress toward said goals Today, investors remain challenged by the lack of standardization of disclosures. Not only are ESG disclosures currently occurring on a voluntary basis, leaving the worst violators the option to simply remain silent, but also, the disclosures themselves are not standard. The ability to compare companies to each other remains a challenge and the ability for a company to greenwash their disclosures still remains a possibility under current regulations. In the United States, the Securities and Exchange Commission and other regulatory bodies must not only grapple with what disclosures should be required but also with how those disclosures should be presented for purposes of uniformity as well as what is considered a material breach of disclosures. To make matters even more complicated, they must also set out the disclosure of supply chain and vendor data as well as uncompensated costs to the environment, society and stakeholders. This is an ongoing journey, but one whose importance is expected to continue to grow.